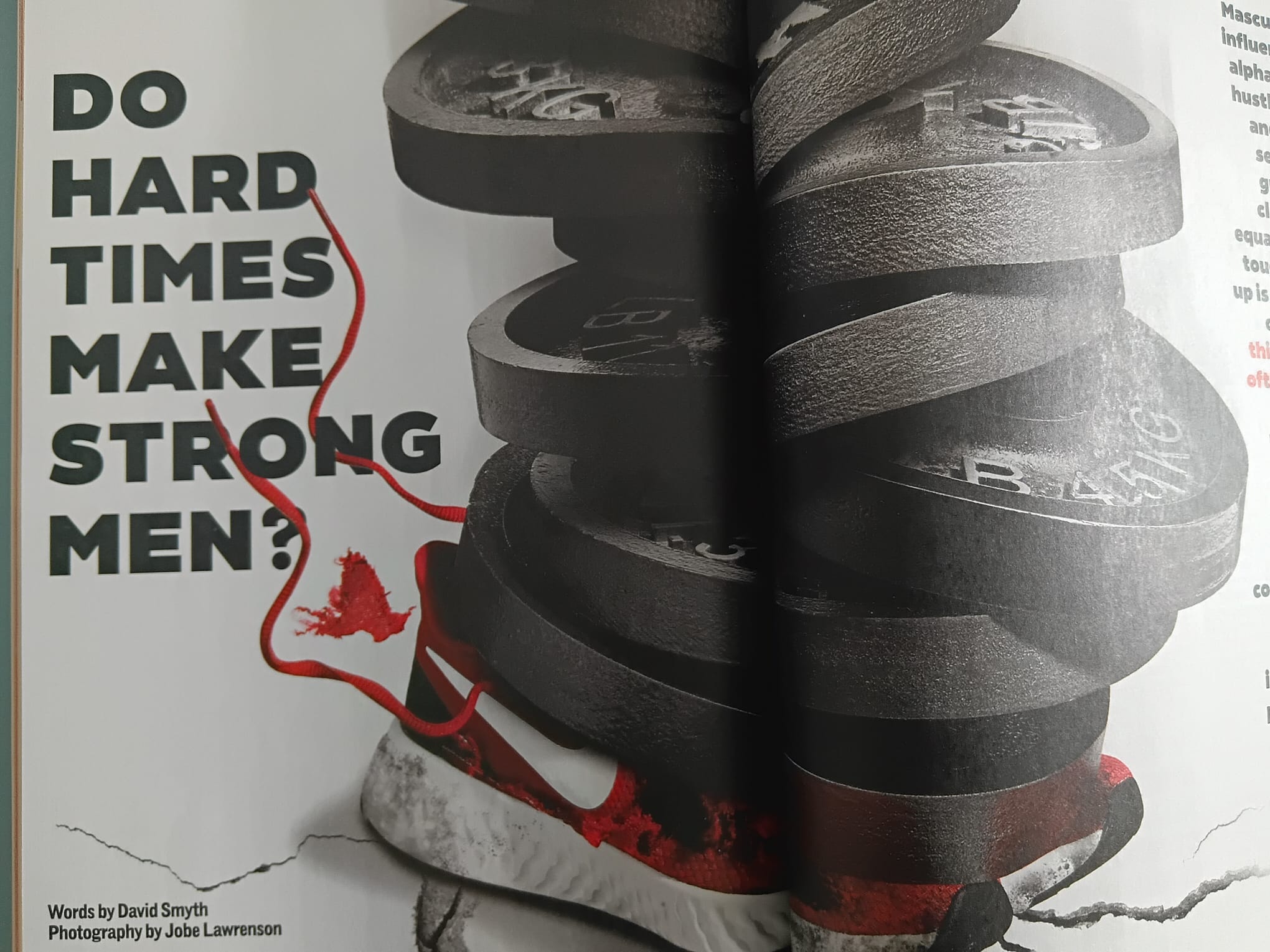

DO HARD TIMES MAKE STRONG MEN? – Men’s Health, Sept 2025 issue

When my wife, for my birthday, bought me a thin mat covered in spikes, I thought it was her way of telling me she wanted a divorce. It’s called an acupressure mat, a modern twist on the ancient bed of nails, with hundreds of pointed plastic discs which dig into your back and neck. At first it hurts, but after a few minutes a warm feeling arrives and it becomes bizarrely, incredibly relaxing. I try lying on it for a while before bed and getting off to sleep starts to be far easier.

Pain first, reward later. Eat your vegetables or you won’t get any pudding. That’s not an outlook that’s easy to maintain in daily life, especially today when yet another dopamine hit is just a finger swipe away. A chorus of voices, from both tough guy masculinity influencers and the comparatively staid world of self-improvement literature, says that if you want to build physical and emotional resilience, you need to add some discomfort to your days.

At the weirder end of the spectrum there are the alpha male hustle bros, apparently competing to see who can get up the earliest like children on Christmas morning. Fitness influencer Ashton Hall went viral this year for a ludicrous routine that found him rising before 4am, rubbing banana peel on his face and saying large numbers to a laptop screen by 9, but surely omitted to show him nodding off in a puddle of his own drool at 4pm. He was only following the moonlit path laid by Mark Wahlberg in 2018 (‘2.45am – Prayer time’!) and go-getters of history such as Benjamin Franklin (5am: ‘Rise, wash and address Powerful Goodness!’ Franklin wrote in the late 1700s).

My intention, being neither a Hollywood A-lister or an 18th Century polymath inventor, is to find out whether some level of elective self-punishment can make an ordinary life more manageable. If my day-to-day routine gets a bit harder, and specifically if I work towards a goal challenge that is significantly beyond my comfort zone, what will that do to my overall state of mind? Can you acquire resilience or do you need to be born with it?

I hesitate to admit this among the mighty bicep owners of Men’s Health magazine, but I am a beta male. You could definitely beat me up. I have the upper body strength of a Cornetto and spend more hours per year in the optician’s than the gym. I am a decent runner, however, with over a dozen marathon medals in a shoebox, so I do know what it’s like to train for something difficult. To make tangible changes to my life, I start looking for a challenge that will be even harder but not impossible, and someone to help me to get ready for it.

The American author and podcaster Michael Easter believes that people should take on regular daunting challenges to expand their resilience. He calls such undertakings ‘misogis’, after the Japanese Shinto ritual of purification, and also compares them to the vanishing concept of the rite of passage. ‘Each time we would take on one of these challenges, we’d go beyond the edges of what we thought we were capable of. And by surfing those edges, we’d find that we’re capable of more than we realized,’ he writes. In his 2021 book The Comfort Crisis he travelled to Alaska to hunt and shoot a caribou and carry its heavy carcass on his back to camp. Crucially, he notes that the benefits are more than just physical: ‘Misogis are an emotional, spiritual and psychological challenge that masquerade as a physical challenge.’

Similarly, you can probably guess the takeaway message of the book titled Do Hard Things by elite athletics coach Steve Magness. ‘Research consistently shows that tougher individuals are able to perceive stressful situations as challenges instead of threats,’ he says. Then there’s Anti-fragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, which claims: ‘Difficulty is what wakes up the genius.’

To wake up my genius I connect with Farren Morgan. He’s a physical trainer based near Southend who served for a decade in the British Military including the Queen’s Guard and the Paratroopers. His training business, The Tactical Athlete, is going to ‘tighten the bolt’, as he puts it, on my lifestyle over the coming month. During this month I’m also going to take part in a Backyard Ultra, a ‘last one standing’ race where competitors run a 4.167 mile course on the hour every hour until only one person can carry on. The distance is set because if you can manage 24 of them in a row you’ll have run exactly 100 miles over a full day. This year the Polish ultrarunner Łukasz Wróbel set a staggering new record for the format: 116 laps, covering over 480 miles in four days and 20 hours. Even if I can manage eight laps I’ll have run further than I ever have before.

Farren has a better idea than me of what the pain of endurance at that level must feel like. When we meet he is not long back from a Land’s End to John o’ Groats challenge for the veterans charity REORG. He covered the length of Britain in 25 days, but made it more interesting by carrying a 35lb pack and adding enough additional distance to turn the traditional 874 mile route into a nice round 1,000 miles. He credits his own resilience to childhood fishing and hunting trips with his grandad: ‘He was getting me up very early when I didn’t want to get up, taking me to cold environments. Maybe if I hadn’t had somebody who put me in those situations, I might not have built that resilience at a young age.’

Later, in the Army, it turned out being ‘on stag’ was great preparation for having his baby. ‘Stag’ is slang for ‘standing guard’, often two hour stints in the middle of the night looking out for a group which is asleep. ‘They inflict lots of sleep deprivation on you in training,’ he says. ‘When you’re in the thick of it you don’t think you’re learning anything from it but you are.’

The British Army has an Adventurous Training Leadership and Resilience programme, training courses involving outdoor sports such as kayaking or mountaineering that are designed to improve resilience, coping strategies and courage. ‘The military are very good at this,’ explains Anthony ‘Staz’ Stazicker, a former Special Forces operator who now runs the technical clothing brand Thrudark. ‘They induce stress across sleep, food and environment, so you’re tired, you’re hungry, you’re cold and wet, and then they’ll layer on complex tasks where you need to make good decisions. When they strip away all the comfort, it removes people’s masks and you can see who they really are. And when people understand a bit more about themselves and how they react in stressful situations, that builds resilience.’

Throughout history there are examples of people who earned respect for rejecting comfort. Diogenes, an ancient Greek who was one of the first Cynics, earned lasting fame for walking barefoot, living inside a large jar and daring to be snarky to Alexander the Great. The Stoic thinkers came later, notably the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, who wrote: ‘The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.’

Or what about poor old Sisyphus, rolling his boulder up a mountain only for it to roll back down again for all eternity? The French philosopher Albert Camus put a new spin on this tale in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus: what if the cursed Greek was having a good time? ‘The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart,’ he wrote. ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’

So it’s not about reaching the victory, it’s about embracing the struggle. Maybe we could all ease off the binge-watching and Deliveroo slightly and struggle a bit more. Farren has a plan for me that is going to be a shock to my system. After a chat on the phone he sends me the longest Whatsapp message I’ve ever received, containing my instructions for the weeks ahead.

To summarise the new developments, he wants me to start getting up between 5 and 6am every day and go to bed around 9pm. He wants my phone to be switched off for at least the first hour I’m awake and the last hour before sleep. He says I need to begin each day with a cold shower for as long as I can stand it, trying to improve on my time by at least five seconds each day. Before I start thinking about work I should be journalling, writing by hand in a notebook: ‘I find it helpful to clear your head in the morning, getting things off your mind. Also, in the evening, it’s great before you sleep to write things down so that you don’t take those thoughts into your sleep,’ he says.

He also sends me a meal plan to make changes to my diet, which I admit is generally poor due to me not bothering to cook something different from the limited selection my teenage children will willingly eat. He wants the protein to ramp way up – so many eggs! – and the carbs to go way down. No alcohol, very little sugar.

Finally, first thing in the morning and also in the evening, he has planned workouts for me. Plenty of running, which is no problem, but also stretching, which I tend to neglect, and strength exercises which I can do at home – lots of embarrassingly difficult push-ups, pull-ups, squats, burpees and so on. ‘As you can see, there are no silly mornings at 3am, you’re not only having 100 calories a day or any of these wild things that you see online. It’s very structured, just to get you into building habits and to help you build mental resilience, a bit more emotional control, and self-belief,’ Farren writes.

I realise that, at least in this first stage, what I need to make my life harder is someone else to make it harder for me. I’m accountable to Farren. He’s texting me most days to ask me what I’ve been doing and how it’s going. As for the big race, I’ve been ultrarunning-curious for a long time, wondering if I’d be any good at going a really long distance, but have previously only entered and withdrawn from a couple of 50k events before they happened, because I felt I hadn’t had enough time to train. If this magazine wasn’t telling me to do the Backyard Ultra, I’d probably just talk about it hypothetically for a few more years.

I talk to Jason Alexandre, a training officer at the Samaritans who runs courses in resilience for people who do stressful jobs. He agrees that there is a social side to resilience, beyond inner toughness: ‘Men are good at the physical stuff, but as well as investing in your body you need to invest in your social connections,’ he advises. ‘If you have people who you are comfortable talking to about your weaknesses, and cheerleaders around to support you, you will be better able to cope with hard things.’

I also phone Mark Cockbain, who is one of the best in the country at making willing victims do horrible things. Having completed over 100 ultramarathons himself, including the 320-mile Yukon Arctic Ultra and a double crossing of the Badwater Ultramarathon in California’s Death Valley, he began devising homegrown challenges that push the limits of physical and mental endurance for others. The best-known is The Tunnel, which consists of 200 miles back and forth inside the mile-long Combe Down tunnel in Bath.

I want to know what characteristics the men and women who attempt his events share. ‘It’s a bit of a cliché, but you can tell some people have got that eye of the tiger,’ he says. ‘You know they want it. Some people hit their lowest point and that’s where they give up, but others come out the other side and find they can keep going. You can push yourself a lot further than you think, but you have to want to do it.’

As my new routine becomes familiar, I start to love the early mornings. Okay, I’m not quite managing 5am, but I am getting at least an hour completely to myself before others in my family emerge, and I even start enjoying the cold showers. It’s bracing under the water and afterwards there’s an amazing glowing feeling, like every blood cell is rushing forwards to hurry me back to warmth. I meet up with Farren to go rucking in his local woods – hiking-slash-jogging wearing 35lb backpacks – and it feels easier than I expected.

However, it becomes apparent that I’m not really gaining an extra hour, because I’m losing one at the other end of the day. By the early evenings I’m flagging, finding it difficult to hold conversations and feeling stressed if I’m not going to make the required bedtime because there’s still too much to do. I am on my phone less but this means I haven’t called my dad back and have lost my impressive Duolingo streak. I’m also feeling healthier from the diet but getting hungry more often, and this makes me irritable.

I’m quicker to snap at my family for this reason and also because of the Ultra race. It’s completely dominating my thoughts like a looming exam, or a murder trial. At my village running club a friend tells me he’s never seen me nervous before a race before. Normally all I have to do is run as fast as I can, and even a marathon is over in a relatively short space of time, so the pain is finite. In a Backyard, the goal is to keep going until you can’t take another step, and I don’t know what that looks like.

Farren asks me what I see myself doing. I say I would be happy with 12 laps, or 50 miles, which would be twice as far as I’ve ever gone before. He says: ‘Okay, then that’s where the race starts.’ He wants me to find my breaking point, but at the same time, I really don’t want to break. I have things to do next week. Shattering into a million pieces will be really inconvenient.

On race morning, in Stanmer Park near Brighton, people are pitching large tents and setting out food and drink like they’re going to be here a very long time. I effectively ram-raided Tesco the day before, diet be damned. I’m doing an Ultra – hell yes I can have Tangfastics.

The bell rings to start lap one. ‘That was a bit of an anticlimax,’ says one competitor, as we all plod away at around 12-minute mile pace then start walking at the first incline. For many hours to come, I find it enjoyable. The slow pace means I can chat to those around me. As we restart each lap at the same time, there are no lonely periods. No one feels like a rival because even hours in, there’s weirdly no way of knowing who is winning. You could finish each four-mile lap in 35 minutes or 59 and have an equal chance of being the last one left at the end.

The hour-long chunks become familiar smaller segments – 10 minutes to the gate, 10 more to the pylon, walk this bit, 8 more minutes to the turnaround. The miles tick away without feeling that far. I know I will see friendly faces at base for roughly 10 minutes every hour – a succession of local running buddies and my amazing wife, who was born to crew. One crucial element of resilience, I discover, is having suffered before, which might be why older people tend to be good at ultrarunning. I find I can push further by reminding myself that I have felt worse than this while trying to run a fast marathon. My legs have ached more in the past.

Gradually, my goalposts move. At midnight, after 12 laps, I want to do three more so I can pass 100km. Then I start thinking about the 5am lap, because it would be wonderful to run at sunrise. But shortly after 4am, a little way into lap 17, I turn around and trudge back to the start. I’m not broken, but a deep tiredness has come over me. I simply feel like I’ve done enough, and sufficiently proud to have covered 66 miles or 107km – far more than I had dared hope.

In the days that follow, it feels like taking off that 35lb rucking pack. I’m lighter, brighter, much nicer to everyone at home. I’ve accomplished something genuinely hard and now I can bask in it. With my running, it feels like a new door has opened after many years of doing the same things. What else could I achieve? Where could I go? My overall mindset also feels a bit more positive. When I learn I will soon lose a regular bit of work that I’ve been doing for the past decade, I find myself feeling optimistic about what I will do with the extra time I’ll gain.

I get slack with the diet and routine, I confess. At first I feel I deserve to indulge myself, and then it is easy to slide back. But I am getting up at more like 6am and I’m keeping the phone rule, barely drinking alcohol, still trying to journal or at least read a book, and I think I’ll even keep the cold showers.

What I like best is the early morning workouts, getting outside when there’s barely anyone else around. The low sunlight strobes through the hedgerows and my shadow stretches out long in front of me. It looks like I am taking up more space in the world.