Terroll Lewis’s equipment at his Brixton Street Gym may look rudimentary compared to the armies of machinery at your average high street joint – bars and tires in a converted loading bay on Somerleyton Road – but it’s nothing compared to the place where he started working out. In Belmarsh Prison, where he served time between 2008 and 2009 for involvement in a gun murder for which he was eventually cleared, it was his bed, his bin and his toilet seat that provided platforms for his dips and press-ups.

“I first started working out in my cell,” he says. “I started doing calisthenics as something to do. That was my meditation – my time away from time.”

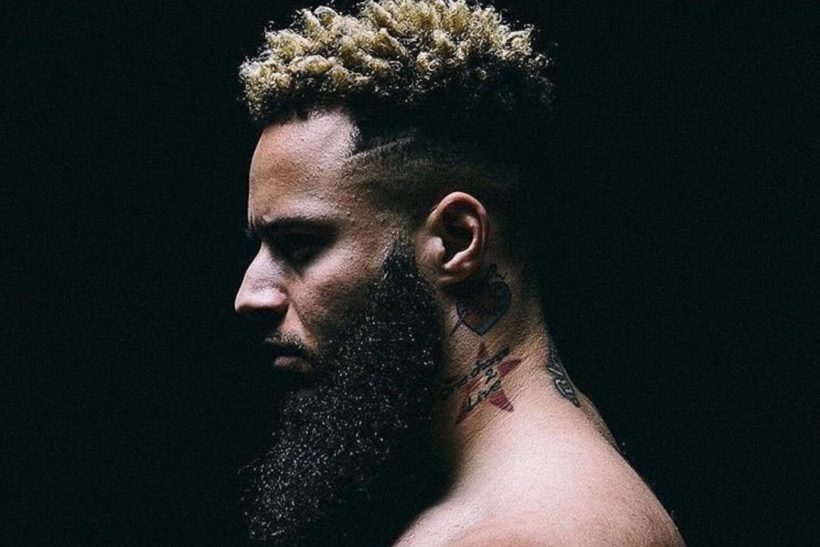

Before then, there was no time for exercise, only robbery and drug dealing as “Boost”, a high ranking member of Brixton’s notorious street gang OC. It stood for “Organised Crime” when he was a young boy, looking up to the wealth-flaunting older lads who loitered around the Myatts Field estate where he lived with his grandparents, and later “One Chance”. He has “One chance 2 live” tattooed on his neck inside a red star.

Now 31, his life was violent even before he was born. When his mother was seven months pregnant with him, aged 21, a man punched her in the face and threw her over a balcony. When Lewis was seven, she was sending him out to buy cannabis for her and also smoking crack cocaine. She has recovered since, but he mostly grew up with her Irish parents. He rarely saw his father. “I had a wild upbringing and was exposed to a lot of stuff. This is before the gangs: this was domestic violence in the household,” he says. “I didn’t have any father figure to guide me in the right way, so what I saw around me was what I became attracted to: the streets, the crime, the violence, the noise. I thought they were a good thing at the time.”

He told his story in a powerful book published at the start of 2021, called One Chance: Surviving London’s Gangs. As he talks about his childhood and especially his teens, the shocking details pile up to an overwhelming extent. But it’s also easy to see why, because these things have happened so gradually and from such a young age, he experienced complete immersion. To him they felt so normal they were hard to shake off.

“The book is obviously not glamorising gang life. It’s just telling the story of a boy who’s gone through some real life stuff and real life situations,” he explains. “I want people to understand why kids get involved in these gangs, which is essentially to find the community and family that’s missing from their lives. There is a lot of trauma behind a lot of these young people’s mindsets, which push them down a certain road, and if there are no positive influences, a lack of father figures, a lack of a certain type of energy, it’s one-way traffic.”

He refers several times to the idea of real-life Call of Duty, and there is a sense of young boys playing at war. In Myatts Field, which he and his friends called Baghdad, “The air smelled of gunpowder,” he says. On his first day at secondary school in Stockwell he was carrying a screwdriver and a knife stolen from his nan and grandad’s kitchen drawer. At the same age, 11, he was stabbed for the first time. Anyone looking at a larger map might think that OC and the Peckham Boys gang were from the same place – south London – but in fact they were deadly rivals, guarding their estates against enemy incursions day and night.

He says he was 14 or 15 when he bought his first gun, which he likens to buying a second-hand car. You have to know the right questions to ask. His journey into ever more serious gang life seems to have been a fairly steady descent, though there was a period when he was signed as an apprentice footballer with Stevenage FC and moved to digs in Hitchin, 40 miles north of Brixton. But watching his friends get rich while he was living on beans proved too difficult, and he was soon back in the old life.

The mentality of constant danger led to some scenarios that might sound incomprehensible to anyone outside of this world. When he got a job in a clothes shop on Oxford Street he would hide his knife under a bush on his way to work and pick it up again on the way home. He confesses to hunting someone for days with the intention of shooting him because the other boy touched his chain. When the influence of a local pastor, Mimi Asher, grew and he started attending church regularly, he was initially still carrying a gun in the pews.

Today he advocates trying to understand that way of thinking, rather than lecturing. “We need more conversations with the young people. It’s OK to say, ‘Put down the knife; put down the gun.’ But take the knife or the gun away and that person feels naked. Instead we need to ask, ‘Why are you carrying the knife? Why are you carrying the gun?’”

Isolated in Belmarsh, he turned his thoughts inwards and developed his calisthenics routines. The word comes from the Greek “kállos” and “sthenos” which means “beauty” and “strength” and as we’ve established, you can even find those things with a toilet seat. “Every time I was watching a TV show, I would make sure I knocked out 100 press-ups in the ad breaks – little challenges like that. I just got creative with whatever I had at the time: chucking some bottles of water in my washbag for a bit of weight, doing dips on my bed, anything just to keep moving.”

When Lewis was released from prison he tried to join a branch of Fitness First but was told he would need to set up a direct debit – an alien concept for someone used to stashing his money under his bed – so it was off to the kids’ playground. “I went to a nearby park and I was doing pull-ups on the broken swing, dips on the slide and loads of different things to keep my mind occupied,” he says.

People saw him exercising in public and more and more wanted to join in. “When I was training at the playground, people began to train with me and it became a word of mouth thing. They would invite others down and gradually it grew and grew. I would post about it on Facebook, then we started inviting people down to Brockwell Park. It started as 20 people and before long it was up to 100.”

He called it Block Workout and it has gone on to become a feature in other London parks and cities, attracting all kinds of people but particularly those, like Lewis, who might find a conventional gym financially restrictive. “It brought people from all walks of life together, all different estates together, and there was no trouble at all. It felt like a gang again, but a positive gang – everyone was there to better themselves,” he says. “Just to have that hour or so on a Saturday morning to let off some steam, get active with likeminded people, was amazing. We made so much noise – so much noise.”

The local council couldn’t help hearing. “They wanted to know how we were managing to get so many people down to one place. They actually thought it was some kind of fight club! But we explained it was to work out, and they said they wanted to create a dedicated space for us.”

So Brixton Street Gym was born, a gym for the community that’s a hybrid of the outdoor, improvised workouts that Lewis started out doing, and more organised classes including boxing, spin, dance and sessions for children. “I can’t explain the love and passion that’s in this place,” says Lewis. When opening the new site in 2019, the then Mayor of Lambeth Ibrahim Dogus remarked on what was possible “when our young people are offered the chance of a real alternative and an environment where hard work and commitment are properly nurtured and rewarded.”

It’s a lesson that Lewis has learned himself – the hard way, but he’s in a great place today. “My life’s been a big, big rollercoaster, but it’s a beautiful struggle. It’s all part of my journey,” he says. “Going through all types of weathers, then coming out the other side and being able to tell the story, and lead by example, is what motivates me now.”